Just two prototypes were built before the program was canceled.

Yet, the concept remains one that has earned almost mythical status among Cold War aviation buffs.

This could allow a parasite fighter to provide protection for a bomber well beyond the range of conventional escorts.

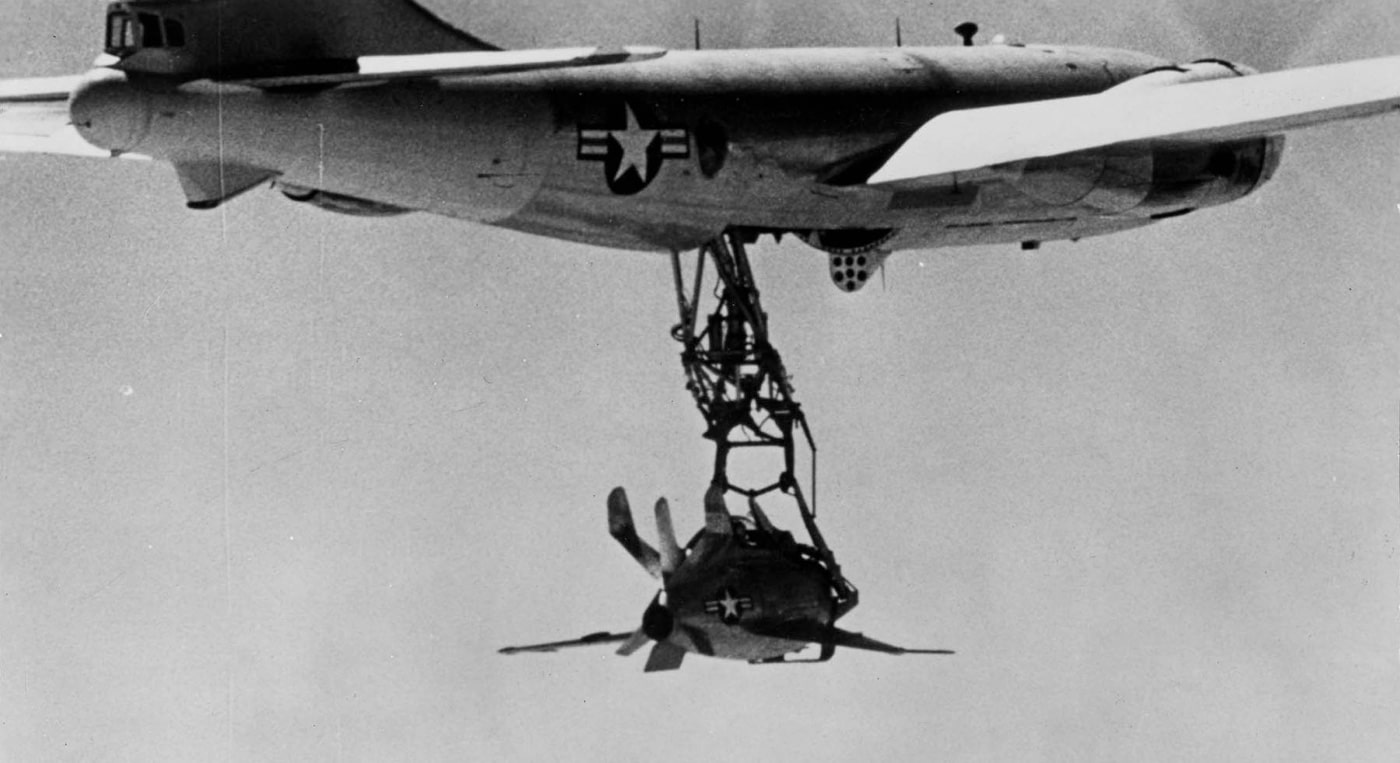

The McDonnell XF-85 Goblin, a prototype “parasite” fighter jet, is shown attached to the belly of a B-29 bomber. This compact aircraft was designed to defend bombers on intercontinental flights. Image: U.S. Air Force

Development of the XF-85 Goblin coincided with the bomber that would carry it: theConvair B-36 Peacemaker.

It could even refuel and be rearmed.

Thus, a small, stout aircraft like the Goblin seemed well-suited to the proposed task.

In this 1948 photograph, test pilot Edwin Foresman Schoch stands next to the XF-85 Goblin. Four of the seven flights of the XF-85 ended with emergency landings. Image: U.S. Air Force

Enter the Goblin

Two single-seat XF-85 prototypes were built for the testing.

The Goblins were unique aircraft and might have seemed to be a leap forward in aviation technology.

It featured five tail surfaces, including one vertical, two angled, and two ventral.

A McDonnell XF-85 Goblin at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio. Image: National Museum of the Air Force

The aircraft also featured swept-back wings that could fold upward.

machine guns, the Goblin would have been reasonably armed for its day.

However, the Superfortress proved to be an ideal platform for the tests, which began in 1948.

Shown here is the second McDonnell XF-85 built for testing and development. Image: National Museum of the Air Force

The higher speed actually made the air even more turbulent.

In one final attempt, the fighters hook missed the trapeze, but the canopy struck it and shattered.

Fortunately, while he made several rough landings, Schoch walked away from each one.

Shown here is the first McDonnell XF-85 Goblin that was built. At the end of each wing, you can see the vertical winglets. Image: National Museum of the Air Force

Testing was ended in late 1949 after just seven flights, totaling two hours and 19 minutes.

Aerial refueling of conventional fighter aircraft was seen as offering greater promise, and the Goblin was grounded.

Could It Have Worked?

Front view of McDonald XP-85 model used for testing. At the time of its development, it was the smallest jet powered airplane in the world. Image: NASA

None of the subsequent efforts proved any more effective, however.

The program ended with the conflict and was put on the back burner.

By contrast, the XF-85 was a major leap forward in technology.

A preserved McDonnell XF-85 Goblin parasite fighter at the U.S. Air Force museum. This compact experimental jet showcases post-WWII aviation innovation. Image: National Museum of the Air Force

Yet, many unanswered questions remain.

As testing didnt progress with the B-36, it remains unclear how any of this could have been accomplished.

Likewise, refueling and rearming in flight was probably easier said than done, especially in the air.

An interior view of the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin’s cockpit reveals its compact design. The tiny workspace highlights the aircraft’s advanced engineering for its role. Image: Ken LaRock/National Museum of the Air Force

Yet, the Fighter Conveyor (FICON) program did move past the testing stage.

Unlike the Goblin, the Thunderflash was too large to be carried internally but hooked underneath the mother plane.

The museum is also home to one of three surviving RF-84K Thunderflash reconnaissance planes.

The XF-85 Goblin, designed for mid-flight deployment, is shown attached to a B-29 bomber during takeoff. Image: National Museum of the Air Force

The other XF-85 Goblin is now on display at the Strategic Air and Space Museum in Ashland, Nebraska.

And perhaps a fitting name for those future drone parasites would be Goblin II!

The XF-85 Goblin is seen deploying from its housing beneath a B-29 bomber. This maneuver tested the feasibility of mid-air fighter deployment for bomber defense. Image: National Museum of the Air Force

The XF-85 Goblin pilot is ready for action, seated in the compact cockpit as the aircraft awaits attachment to a B-29 bomber. Image: National Museum of the Air Force

A close-up view of the wing and hook controls inside the XF-85 Goblin cockpit highlights the precision engineering needed for mid-air deployment and retrieval. Image: National Museum of the Air Force

The YRF-84F flying underneath its B-36 carrier aircraft. FICON modifications included installing a hook in front of the cockpit and turning down the horizontal tail. Image: U.S. Air Force

ARepublic F-84E Thunderjetin an extended parasite position under its host Convair B-36 Peacemaker. Image: U.S. Air Force

View of the YRF-84F from inside the B-36 bomber. The pilot could enter and exit the cockpit from within the Peacemaker. Image: U.S. Air Force

A Bell X-2 rocket plane is dropped from the Boeing B-50 Superfortress mothership during testing in the mid-1950s. Image: NASA